What Happened to the Crew of the Ss Venture

Nifty Eastern at Heart's Content after laying the first transatlantic cable, July 1866 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Name | Swell Eastern |

| Port of registry | Liverpool, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland |

| Ordered | 1853 |

| Builder | J. Scott Russell & Co., Millwall |

| Laid down | 1 May 1854 |

| Launched | 31 January 1858 |

| Completed | August 1859 |

| Maiden voyage | 30 August 1859 |

| In service | 1859 |

| Out of service | 1889 |

| Stricken | 1889 |

| Homeport | Liverpool |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Fate | Scrapped 1889–ninety |

| Notes | Struck rocks on 27 August 1862. No bigger ship in all respects until 1913. |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Rider ship |

| Tonnage | xviii,915 GRT[2] |

| Deportation | 32,160 tons |

| Length | 692 ft (211 m) |

| Beam | 82 ft (25 m) |

| Decks | 4 decks |

| Propulsion | Four steam engines for the paddles and an additional engine for the propeller. Total power estimated at 8,000 hp (six,000 kW). Rectangular boilers[1] |

| Speed | 14 knots (26 km/h; sixteen mph)[3] |

| Boats & landing craft carried | 18 lifeboats; after 1860 xx lifeboats |

| Chapters | iv,000 passengers |

| Complement | 418 |

SS Great Eastern was an fe sail-powered, paddle bicycle and screw-propelled steamship designed past Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and built by John Scott Russell & Co. at Millwall Iron Works on the River Thames, London. She was the largest ship ever built at the time of her 1858 launch, and had the capacity to carry four,000 passengers from England to Commonwealth of australia without refuelling. Her length of 692 feet (211 g) was surpassed only in 1899 by the 705-foot (215 m) 17,274-gross-ton RMSOceanic, her gross tonnage of xviii,915 was merely surpassed in 1901 by the 701-foot (214 m) 21,035-gross-ton RMSCeltic and her 4,000-passenger chapters was surpassed in 1913 by the 4,234-rider SSImperator. The ship's five funnels were rare and were later reduced to 4. The vessel too had the largest fix of paddle wheels.

Brunel knew her affectionately as the "Great Infant". He died in 1859 soon later her maiden voyage, during which she was damaged by an explosion.[four] After repairs, she plied for several years as a passenger liner betwixt United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and North America before being converted to a cable-laying transport and laying the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866.[5] Finishing her life as a floating music hall and advertizement hoarding (for the section store Lewis'southward) in Liverpool, she was broken up on Merseyside in 1889.

History [edit]

Concept [edit]

After his success in pioneering steam travel to Northward America with Slap-up Western and Dandy Britain, Brunel turned his attention to a vessel capable of making longer voyages as far equally Australia. With a planned capacity of 15,000 tons of coal, Great Eastern was envisioned as being able to sheet halfway around the earth without taking on coal, while besides carrying so much cargo and passengers that papers described her as a "floating city" and "the Crystal Palace of the ocean".[6] [vii] Brunel saw the ship as being able to effectively monopolize trade with Asia and Australia, making regular trips betwixt Britain and either Trincomalee or Australia.[7]

On 25 March 1852, Brunel fabricated a sketch of a steamship in his diary and wrote beneath it: "Say 600 ft x 65 ft x 30 ft" (180 m x xx m x 9.1 m). These measurements were six times larger by volume than whatever send afloat; such a large vessel would benefit from economies of scale and would exist both fast and economical, requiring fewer crew than the equivalent tonnage fabricated up of smaller ships. Brunel realised that the ship would need more than 1 propulsion system; since twin screws were still very much experimental, he settled on a combination of a unmarried screw and paddle wheels, with auxiliary canvass power. Although Brunel had pioneered the screw propeller on a big scale with Swell Britain, he did non believe that information technology was possible to build a single propeller and shaft (or, for that matter, a paddleshaft) that could transmit the required power to bulldoze his behemothic send at the required speed.[eight]

Brunel showed his thought to John Scott Russell, an experienced naval architect and transport builder whom he had first met at the Great Exhibition. Scott Russell examined Brunel'southward programme and made his own calculations as to the transport's feasibility. He calculated that it would have a deportation of 20,000 tons and would require 8,500 horsepower (half dozen,300 kW) to achieve xiv knots (26 km/h; 16 mph), but believed it was possible. At Scott Russell'southward suggestion, they approached the directors of the Eastern Steam Navigation Company with the new design plan. The James Watt Company would design the ship'south screw, Professor Piazzi Smyth would blueprint its gyroscopic equipment, and Russell himself would build the hull and paddle bicycle.[seven]

1854–1859: Construction to launch [edit]

Construction [edit]

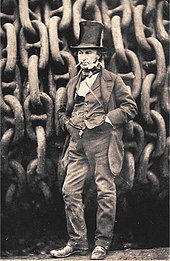

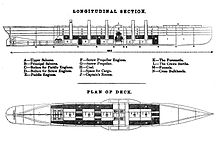

Sectional plan of Great Eastern

Structure of Nifty Eastern, August 18, 1855

Brunel entered into a partnership with John Scott Russell, an experienced Naval Architect and ship architect, to build Swell Eastern. Unknown to Brunel, Russell was in financial difficulties. The two men disagreed on many details. It was Brunel's final great project, and he collapsed from a stroke after existence photographed on her deck, and died only 10 days later, a mere four days later Bully Eastern 'due south first ocean trials. About the ship, Brunel said "I take never embarked on any one thing to which I have so entirely devoted myself, and to which I have devoted so much fourth dimension, idea and labour, on the success of which I take staked then much reputation."

Great Eastern was built past Messrs Scott Russell & Co. of Millwall, London, the keel being laid down on i May 1854. She was 211 metres (692 ft 3 in) long, 25 metres (82 ft 0 in) wide, with a draught of six.1 metres (20 ft 0 in) unloaded and 9.one metres (29 ft 10 in) fully laden, and displaced 32,000 tons fully loaded. In comparison, SS Persia, launched in 1856, was 119 m (390 ft 5 in) long with a 14 m (45 ft 11 in) beam. She was at first named Leviathan, merely her high building and launching costs ruined the Eastern Steam Navigation Company and so she lay unfinished for a year before being sold to the Great Eastern Send Company and finally renamed Great Eastern. Information technology was decided she would exist more profitable on the Southampton–New York run, and she was outfitted accordingly.[9]

The hull was an all-iron construction, a double hull of 19-millimetre (0.75 in) wrought iron in 0.86 thousand (two ft 10 in) plates with ribs every 1.8 m (v ft xi in). Her roughly thirty,000 iron plates weighed 340 kilograms ( i⁄3 long ton) each, and were cutting over individually-fabricated wooden templates before beingness rolled to the required curvature.[7] Internally the hull was divided past two 107 m (351 ft 1 in) long, 18 chiliad (59 ft i in) high, longitudinal bulkheads and farther transverse bulkheads dividing the send into nineteen compartments. Great Eastern was the first ship to contain a double-skinned hull, a feature which would not be seen again in a ship for 100 years, simply which would later become compulsory for reasons of safety. To maximize her fuel capacity, stored coal was bunkered effectually and over her x boilers.[seven] She had sheet, paddle and screw propulsion. The paddle-wheels were 17 m (55 ft 9 in) in bore and the four-bladed screw-propeller was 7.three grand (23 ft 11 in) beyond. The power came from four steam engines for the paddles and an additional engine for the propeller. Total power was estimated at six,000 kilowatts (eight,000 hp). She had six masts (said to be named after the days of a calendar week – Monday being the fore mast and Sabbatum the spanker mast), providing infinite for 1,686 square metres (xviii,150 sq ft) of sails (seven gaff and maximum 9 (unremarkably four) square sails), rigged similar to a topsail schooner with a chief gaff canvas (fore-and-aft sail) on each mast, one "jib" on the fore mast and three square sails on masts no. 2 and no. iii (Tuesday & Wed); for a time mast no. 4 was also fitted with 3 yards. In later years, some of the yards were removed. According to some sources she would have carried five,435 grandii (58,500 sq ft) in sails.[ who? ] Setting sails turned out to exist unusable at the aforementioned time equally the paddles and spiral were nether steam, because the hot exhaust from the 5 (subsequently four) funnels would set them on burn down. Her maximum speed was 13 knots (24 km/h; xv mph). She was involved in a serial of accidents during construction, with 6 workers being killed.[10]

Launch [edit]

Great Eastern before launch in 1858

Manus-coloured lithograph of the SS Great Eastern, the bully send of IK Brunel as imagined by the artist at her launch in 1858

Great Eastern was planned to exist launched on 3 November 1857. The transport's massive size posed major logistical issues; according to one source, the ship's nineteen,000 tons (12,000 inert tons during the launch) made it the single heaviest object moved by humans to that signal.[9] On three November, a large crowd gathered to watch the ship launch, with notables nowadays including the Comte de Paris, the Duke of Aumale, and the Siamese ambassador to United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland.[ix] The launch, however, failed, and the send was stranded on its launch rails – in addition, ii men were killed and several others injured, leading some to declare Great Eastern an unlucky ship. Brunel rescheduled the launch for January 1858, hoping to use the tide in the adjacent launch endeavour.[9]

In the leadup to the second launch, Brunel and Great Eastern's backers gathered a pregnant number of bondage, jacks, hydraulic rams, and windlasses to assist in launching the ship. Some were obtained from sympathetic engineers, others through returned favours, and yet more for increasing sums on money; so lucrative was renting out of supplies for the ship'due south launch that engineer Richard Tangye was able to found his own engineering firm (Tangye & Co) the next year, remarking that "Nosotros launched Great Eastern, and she launched u.s.". [nine] Advice sent to Brunel on how to launch the ship came from a number of sources, including steamboat captains on the Dandy Lakes and one gentleman who wrote an insightful description on how the massive Bronze Horseman had been erected in Saint petersburg.[9] High winds prevented the ship from being launched on xxx January, but the adjacent morning a fresh try successfully launched the transport around 10:00 in the morning.[9]

Post-obit her launch, Not bad Eastern spent a further 8 months beingness fitted out. However, the cost of the plumbing equipment out ($600,000) concerned many investors, who had already spent nearly $6,000,000 amalgam her.[11] With the building company already in debt, cost cutting measures were implemented; the ship was removed from Russell's shipyard, and many investors requested she exist sold. As reported past the Times, one investor openly proposed that the transport be sold to the Royal Navy, noting if the navy employed Bang-up Eastern every bit a ram, she would easily cleave through whatsoever warship afloat.[11] These efforts had mixed success, with the ship somewhen being sold to a new visitor for £800,000, equating to a loss of $three,000,000 for investors in the Eastern Steam Navigation Company.[4] The new company modified parts of its predecessor'due south design, most notably cutting the send'southward coal chapters as it intended to apply the send for the American market. Fitting out concluded in Baronial 1859 and was marked with a lavish banquet for visitors (which included engineers, stockholders, members of parliament, 5 earls, and other notables).[4] In early September 1859, the ship sailed from her dock towards the channel, accompanied by many spectators. Nonetheless, off Hastings she suffered a massive steam explosion (caused by a valve being left close by blow later on a pressure test of the system) that killed five men.[4] She proceeded to Portland Bill and then to Holyhead, though some investors claimed more money could have been made if the send had remained as an "exhibition send" for tourists in the Thames.[four] Corking Eastern successfully rode out the infamous Royal Charter Storm, after which it was moved to Southampton for the winter.[4] The get-go of 1860 led to a farther alter of buying when the owning company was institute to be badly in debt and the value of the ship depreciated by half. This revelation forced the resignation of the lath of directors, who were then replaced by a third group of controlling stockholders.[4]

With the new board in identify, the send was recapitalized to raise an boosted $fifty,000. The new board was determined to end the transport, merely besides betted heavily on making large profits exhibiting the ship in North American seaports. To accomplish this, the company played major American and Canadian cities confronting each other, goading them into competition over which metropolis would welcome Peachy Eastern; the city of Portland, Maine (with boosted investment from the Grand Torso Railroad) went then far as to build a $125,000 pier to adjust the ship.[12] Ultimately New York City – which had apace dredged a berth for her aslope a lumber wharf – was decided on as the ship'southward outset destination.[12]

1860–1862: Early career [edit]

After some delays, Neat Eastern began her 11-day maiden voyage on 17 June 1860, with 35 paying passengers, eight company "dead heads" (passengers who do not pay) and 418 crew. Amongst the passengers were two journalists, Zerah Colburn and Alexander Lyman Holley. Her first crossing went without incident, and the send'southward seaworthiness was proven once more when she easily survived a pocket-size gale. Great Eastern arrived in New York on 28 June and was successfully docked, though she did damage part of a wharf. The transport was received with bang-up aplomb, with many vessels and tens of thousands of people crowding to see her. In preparation for the crowds, the crew established a bar on deck, spread sand to soak upwardly tobacco juice, and prepared to receive thousands of visitors. However, relations between the crew and New Yorkers began to sour – the public was outraged by the $1 entry fee (similar excursion trips in New York charged 25 cents) and many would-be visitors decided to forego visiting the ship.[12] Bully Eastern left New York in late July, taking several hundred passengers on an excursion trip to Cape May then to Old Betoken, Virginia.[13] However, this too raised problems as the ship did non take enough provisions (a outburst pipe in a storeroom had ruined much of the send'southward food) to make the short trip comfortable, while the transport's rudimentary bathrooms posed a sanitation issue.[14] Duplicate tickets were sold for some berths, families were separated and remixed in improperly assigned cabins, and five plainclothes police officers (put on past New York to deter pickpockets) were discovered and chased into a livestock pen on deck.[14] After reaching Virginia, the transport steamed dorsum to New York, and from there sailed southward again for an excursion prowl in the Chesapeake bay. The ship departed for Annapolis, where it was given 5,000 tons of coal past the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.[fifteen] Cracking Eastern remained in Annapolis for several days, where she was toured by several thousand visitors and President James Buchanan. During the presidential visit, i member of the company board discussed sending the ship to Savanah to transport Southern cotton to English mills, but this idea was never followed upwards on.[15]

Upon its second return to New York, the company decided to sail from the United States. From a financial perspective, the American venture had been a disaster; the ship had taken in simply $120,000 against a $72,000 overhead, whereas the visitor had expected to take in $700,000. In addition, the company was facing a daily involvement payment of $5,000, which ate into any profits the ship made.[15] Hoping to cyberspace more profit before returning to United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, the ship sailed from New York in mid August, jump for Halifax with 100 passengers. However, on approach to the port the ship was hailed by a local lighthouse service, which was empowered by police force to collect a price based on ship tonnage – given the size of the ship, the lighthouse levied a toll of $one,750 on Groovy Eastern. Infuriated by the size of the toll, a party went ashore to asking that the toll be waived, but the governor of Halifax denied this request. Angered past the refusal, the helm and company leadership ordered the ship to return to Britain immediately, and as such no passengers or visitors were taken on in Halifax.[16]

With the applied science success only financial failure of the 1860 trip, the ship'due south ownership visitor again attempted to turn Great Eastern profitable. During the winter of 1860, Scott Russell (who had recently won a $120,000 legal judgement against the ship company) refitted the transport and repaired damage sustained during its kickoff year of operations; during the refit, she once broke gratis from her moorings and cut off the bowsprit of HMS Blenheim.[17] She departed for New York in May 1861 (her other potential port, Baltimore, at present considered too risky due to the outbreak of the American Civil War), arriving in the port with little fanfare. Taking on a cargo of v,000 tons of barrelled wheat and 194 passengers, she departed for Liverpool on 25 May, making an uneventful trip.[18] Upon her return to Britain, it was announced that the ship'due south company had been contracted by the British War Office to ship 2,000 troops to Canada, function of a show of force to intimidate the quickly-arming United States. Afterward a further refit to carry troops, Great Eastern departed Britain for Quebec Metropolis carrying 2,144 soldiers, 473 passengers, and 122 horses; according to 1 source, this number of passengers – when coupled with Keen Eastern's crew of 400 – marked the well-nigh number of people aboard a single ship to that point in history.[18] The voyage was a success and the ship made information technology to Quebec, where it took two days for the city's steamers to ferry the passengers from the ship. The crossing was made in record-setting time, taking 8 days and half dozen hours. Swell Eastern's durable design was praised past the military officers aboard, merely soon after her return to Britain the War Office discontinued the contract, and the send returned to regular passenger service.[eighteen]

In September 1861, Groovy Eastern was caught in a major hurricane two days out of Liverpool. The send was trapped in the storm for three days and suffered major damage to her propulsion systems; both her paddle wheels were torn off, her sails stripped away, and her rudder had been aptitude to 200 degrees and subsequently torn upwardly by the ship's unmarried propeller. A jury-rigged propeller was installed past Hamilton Towle (an American engineer returning from Republic of austria), assuasive the ship to steer for Ireland powered but by her screw. Arriving in Queenstown, (at present Cobh), she was denied entry to the harbour as information technology was feared high winds would cause her to smash her anchorage; she was granted entry three days later on and towed in by HMS Advice, trigger-happy the anchor off an American merchant on her way to her berth. The only fatal casualty of the prowl occurred in port when a human being was killed past backspin off the helm. Damage caused by the storm and lost revenue from the trip amounted to $300,000.[19]

The transport connected a cycle of uneventful cruises, cargo loadings, and cursory exhibitions from tardily 1861 to mid 1862. By July 1862, the send was turning its first noteworthy profits, conveying 500 passengers and eight,000 tons of foodstuffs from New York to Liverpool, bringing in $225,000 in gross and requiring a turnaround of only xi days. However, as noted by sources, the ship'south owners struggled to sustain this profitability as they were heavily focused on upper and center grade passenger service. Equally such, the ship was non used to transport large groups of immigrants travelling to the United states, nor did it take full advantage of the major downturn in the American clipper industry during the American Civil State of war.[twenty]

1862–1884: Later career [edit]

Berthed at New York, 1860

Great Eastern Rock incident [edit]

On 17 August 1862, Corking Eastern departed from Liverpool for New York, conveying 820 passengers and several thousand tons of cargo – given the size of her load, she was drawing ix metres (30 ft) of h2o.[21] After outrunning a small squall, the ship approached the New York declension on the dark of 27 August. Fearing that Nifty Eastern was resting too low in the water to pass past Sandy Claw, the ship'southward helm instead chose the nominally safer route through Long Isle Audio. While passing by Montauk Point effectually ii:00 AM, the transport collided with an uncharted rock needle (later named Great Eastern Rock) that stood around 8 metres (26 ft) above the surface. The rock punctured the outer hull of the ship, leaving a gash 2.7 metres (9 ft) wide and 25 metres (83 ft) long—it was later calculated that the needle was large enough to contact the inner hull, only that the outer hull and stiff transverse braces had prevented the inner hull from being breached. The standoff was noticed by the crew, who guessed that the ship had struck a shifting sand shoal, and subsequently a bilge cheque Not bad Eastern continued onto New York without incident.[22] While in port, nonetheless, it was noticed that the ship had acquired a slight list to starboard, and so a diver was sent in to inspect the hull. Later several days of inspection, the diver reported the massive pigsty in the ship'southward outer hull, a major issue as no drydock in the world could fit the ship.[21] The ship'southward hull was repaired by metalworkers in a cofferdam, but toll the visitor $350,000 and delayed the ship's render to Britain past several months.[21] She would brand one more trip to New York and back in 1863 earlier being laid upwardly until 1864 due to her operating costs.[23]

In January 1864, it was appear that the send would be auctioned off. During the auction, four members of the company board of directors bid $125,000 for the transport and won it, thus acquiring personal control of the vessel. The group then allowed the transport company to go bankrupt, thus separating the ship from the now defunct aircraft company and divesting many smaller stockholders. The send was then contracted out to Cyrus West Field, an American financier, who intended to use it to lay underwater cables.[23] A trend soon emerged in which the ship's owners would rent out Not bad Eastern as a cable layer in exchange for shares in cable companies, ensuring that if Neat Eastern succeeded in laying cables, the unprofitable ship could be personally lucrative for her owners.[23]

Cable laying [edit]

In May 1865, Keen Eastern steamed to Sheerness to have on wire for the laying of the Transatlantic telegraph cable. In return for using the ship, her owners wanted $250,000 in telegraph company stock, but simply on the condition the wire laying succeeded.[24] To arrange the 22,450 kilometres (13,950 mi) of cable she was carrying, Great Eastern had some of her salons and rooms replaced with large tanks to hold the cable. In July the ship began laying the undersea cable near Valentia Isle, gradually working its way west at a speed of 11 km/h (6 kn). The attempt went relatively smoothly for several weeks, but the cable end was lost mid-Atlantic in an blow, forcing the ship to return in 1866 with a new line. The ship's first officeholder, Robert Halpin, managed to locate the lost cable end and the unbroken cable made it to shore in Heart's Content, Newfoundland on 27 July 1866.[24]

Halpin became captain of Great Eastern, with the ship laying further cables.[25] In early 1869 she laid a series of undersea cables almost Brest.[26] After that year she was outfitted to lay undersea cables in the Indian Sea; most of the operation's expenses were covered by the British government and banks in India, which hoped to circumvent the unreliable overland cables linking U.k. to Republic of india.[xiii] In preparation for operations in the hot climate, the send was painted white to deflect heat abroad from the transport's cable tanks. Great Eastern departed from Great britain in December 1869, arriving in Bombay (now Mumbai) 83 days afterward to lay her first cable anchor. Upon its arrival in port, Groovy Eastern's size generated considerable public involvement, with the captain offering tickets to view the transport for 2 rupees apiece, distributing gain to the crew.[13] Parting from Bombay before the onset of the Monsoon season, she proceeded north to lay a cable between Bombay and Aden. From Aden, she laid another cable to the island of Jabal al-Tair, where a 2nd ship rendezvoused with her to take up the cablevision to Suez and then on to Alexandria.[13]

Suez Canal concerns [edit]

The Suez Canal, which opened in 1869, was a setback for the transport: the transport was too wide for the canal, and going around Africa it would not exist able to compete with ships that could use the canal. One famed Arab navigator proposed taking the ship through the canal, but this was never attempted.[13]

1885–1890: Interruption upwards [edit]

Not bad Eastern equally a floating billboard for Lewis's Department Shop in Liverpool, 1880s

Smashing Eastern beached for breaking upward

At the end of her cable-laying career – hastened by the launch of the CS Faraday, a ship purpose congenital for cable laying[13] – she was refitted as a liner, merely once over again efforts to make her a commercial success failed. She remained moored in Milford Harbour for some time, abrasive the Milford harbour board, which wanted to build dockyards in the area. Many proposals for the transport were raised; according to 1 source, pubs were full of talk of filling her with gunpowder and blowing her up.[27] The ship was ultimately saved, however, as a dock engineer (Frederick Appleby) was able to build a dock effectually her, using the ship'south massive blob as a station for driving pylons. During her 11 years moored in Milford, she accrued a big amount of biofouling on her hull. Early marine naturalist Henry Lee (best known at the time for his skepticism towards bounding main monsters) conducted an extensive study of her hull, calculating she had ~300 tons of marine life attached to her.[28] She was sold at sale, at Lloyd'due south on 4 November 1885, past order of the Courtroom of Chancery. Bidding commenced at £10,000, rising to £26,200 and sold to Mr Mattos, a city merchant.[29]

Sold over again, she was used as a showboat, a floating palace/concert hall and gymnasium. She later acted every bit an advertising hoarding—sailing up and down the Mersey for Lewis'southward Department Store, who at this point were her owners, before beingness sold.[30] [31] The thought was to attract people to the store by using her as a floating visitor allure. In 1886 she was sailed to Liverpool for the Liverpool Exhibition of 1886 – during the transit, she struck and badly damaged 1 of her tugs, the terminal of 10 ships she would impairment or sink.[32] Sold again later the exhibition, i visitor considered using her to raise shallow shipwrecks, while one humorist suggested that Nifty Eastern be used to help dig the Panama canal by ramming her into the isthmus.[33] She was, again, sold at auction in 1888, fetching £16,000 for her value every bit chip.[34] [35] Many pieces of the ship were bought by private collectors, quondam passengers, and friends of the coiffure – diverse fixtures, lamps, furniture, paneling, and other artifacts were kept. Parts of Great Eastern were repurposed for other uses; one ferry company converted her wood paneling into a public house bar, while ane mistress at a Lancashire boarding school acquired the ship's deck caboose for use as a children'south playhouse.[13]

An early example of breaking-up a structure by use of a wrecking ball, she was scrapped nearly the Sloyne, at New Ferry on the River Mersey by Henry Bath & Son Ltd in 1889–1890—it took 18 months to take her apart, with her double hull being particularly difficult to salve. The breaking of the ship caused a minor labour dispute as workers – who were paid by the ton of ship scrapped – became frustrated with the slow pace of breaking and went on strike.[36]

Trapped worker legend [edit]

After Bang-up Eastern's scrapping, rumours spread that the shipbreakers had found the remains of trapped worker(s) entombed in her hull—likely inspired past tales spread by her crew of a phantom riveter who had been sealed in the ship'due south hull. The legend was kickoff widely noted on by James Dugan in 1952, who quoted a letter from a Captain David Duff, and many later sources cite Dugan's work. Other authors, notably Fifty. T. C. Rolt in his biography of Brunel, have dismissed the claim (noting such a discovery would have been recorded in visitor logs and received press attention), but the legend has become widely mentioned in books and manufactures about nautical ghost stories.[37] Brian Dunning wrote nigh the fable in 2020, noting that while it was technically impossible to evidence or disprove, the incident could not have happened given the lack of evidence being found during the numerous times Bang-up Eastern was being repaired. [37]

Surviving parts [edit]

In 1928, Liverpool Football Club were looking for a flagpole for their Anfield basis, and consequently purchased her top mast.[38] It still stands in that location today at the Kop cease.[39] In 2011, the Aqueduct four program Fourth dimension Team establish geophysical survey evidence to advise that residual iron parts from the send'due south keel and lower structure still reside in the foreshore.[twoscore]

During 1859, when Great Eastern was off Portland conducting trials, an explosion aboard blew off one of the funnels. The funnel was salvaged and subsequently purchased by the water company supplying Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in Dorset, UK, and used as a filtering device. It was after transferred to the Bristol Maritime Museum close to Brunel's SS Great Britain and so moved to the SS Slap-up U.k. Museum.

In October 2007, the recovery of a 6,500-pound (2.9 t) anchor in lxx feet (21 grand) of h2o nearly four miles (6.4 km) from Great Eastern rock stirred speculation that information technology may have belonged to Great Eastern.[41]

In popular culture [edit]

- The SS Groovy Eastern is the subject of the Sting vocal, "Ballad of the Neat Eastern" from the 2013 album The Final Ship.

- The history of the SS Great Eastern is chronicled in detail in James Dugan's non-fiction book The Great Iron Ship.[13]

- An Atlantic crossing on the SS Slap-up Eastern is the backdrop to Jules Verne's 1871 novel A Floating Metropolis

- The SS Nifty Eastern and its creator Isambard Kingdom Brunel are cardinal to Howard A. Rodman'due south 2019 novel The Great Eastern, in which Captain Ahab is pitted confronting Captain Nemo.

- The Great Eastern was the name of a radio comedy show on CBC Radio One from 1994 to 1999, named for the steamship.

- In the trade management video game Anno 1800, released in 2019 by Ubisoft, the player has the opportunity to construct Cracking Eastern as an improver to their naval fleet. Great Eastern has the largest cargo capacity of any transport in the game with a total of eight cargo slots.

Gallery [edit]

-

On the deck, 1857

-

Great Eastern,

12 November 1857 -

SS Great Eastern 's launch ramp at Millwall

-

Print referring to the difficulty of trying to launch Slap-up Eastern. The Mariners' Museum

-

Magazine illustration ca. 1877

Encounter also [edit]

- James Henry Pullen's model of SS Great Eastern

- Steering engine – Great Eastern was the first ship and then equipped

- Transatlantic telegraph cable

- Robert Halpin, commanded the SS Bully Eastern when a cable layer

- List of large sailing vessels

References [edit]

- ^ Paradigm:Oscillating engine, and boilers, of Neat Eastern - gteast.gif224kB.png

- ^ Dawson, Philip S. (2005). The Liner. Chrysalis Books. p. 37. ISBN978-0-85177-938-6.

- ^ "Ocean Record Breaking". New York Times. seven July 1895.

- ^ a b c d due east f g Dugan (1952) p. 36-39, 41-49

- ^ Wilson, Arthur (1994). The Living Rock: The Story of Metals Since Earliest Times and Their Impact on Culture. Woodhead Publishing. p. 203. ISBN978-i-85573-301-5.

- ^ Rolt 1957, p. 309

- ^ a b c d e Dugan (1952) p. iii, four, 5, vi

- ^ Rolt 1957, p. 313

- ^ a b c d east f g Dugan (1952) p. 9-17

- ^ "Brunel's ships p147"

- ^ a b Dugan (1952) p. 35

- ^ a b c Dugan (1952) p. 49, fifty-68

- ^ a b c d eastward f 1000 h Dugan, James (1953). The Nifty Atomic number 26 Send. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 222, 223, 224, 240. ISBN978-0750934473.

- ^ a b Dugan (1952) p. 72-79

- ^ a b c Dugan (1952) p. 81-84

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 84, 85

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 88-90

- ^ a b c Dugan (1952) p. 97, 98

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 108-123

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 130-141

- ^ a b c Dugan (1952) p. 139, 145

- ^ Brander, Roy. "The RMS Titanic and its Times: When Accountants Ruled the Waves". Elias Kline Memorial Lecture, 69th Shock & Vibration Symposium . Retrieved 26 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Dugan (1952) p. 160-164, 207

- ^ a b Dugan (1952) p. 172-188

- ^ Taylor, Richard (June 2021). "The Halpin Memorial Medal". Orders & Medals Research Society Journal. sixty (2): 146. ISSN 1474-3353.

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 208-217

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 241

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 246

- ^ "Sale of the Great Eastern". The Cornishman. No. 381. five Nov 1885. p. 5.

- ^ South. R. Hill (4 July 2016). The Distributive Organization: The Commonwealth and International Library: Social Administration, Training, Economics and Production Division. Elsevier. pp. 101–. ISBN978-1-4831-3777-3.

- ^ Brindle, Steven (23 May 2013). Brunel: The Man Who Built the Globe. Orion Publishing Group. pp. 121–. ISBN978-1-78022-648-4.

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 250

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 242

- ^ Graves-Brownish, Paul; Harrison, Rodney; Piccini, Angela (17 October 2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World. OUP Oxford. pp. 250–. ISBN978-0-19-166395-6.

- ^ Hall, David; Dibnah, Fred (31 March 2013). Fred Dibnah'southward Age Of Steam. Ebury Publishing. pp. 89–. ISBN978-one-4481-4140-1.

- ^ Dugan (1952) p. 266

- ^ a b "The Skeletons of the Great Eastern". Skeptoid . Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "New display on Brunel's SS Corking Eastern". Liverpool Museum. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "LIVERWEB – An A to Z of Liverpool FC – G". liverweb.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Presenter: Tony Robinson (x Nov 2011). "Brunel's Last Launch". Time Squad Special. Channel four.

- ^ Drumm, Russell (eleven October 2007). "Mysterious Humongous Anchor Snagged Big haul for dragger off Montauk Bespeak". East Hampton Star. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010.

Further reading [edit]

- Cadbury, Deborah (2003). Seven Wonders of the Industrial World. Fourth Estate. ISBN978-0-00-716304-5.

- Dugan, James (1953). The Dandy Iron Transport. Harper. ISBN978-0-7509-3447-3.

- Emmerson, George Southward. (1981). Southward.S. Great Eastern. David & Charles. ISBN978-0-7153-8054-three.

- Gillings, Annabel (2006). Brunel . Haus Publishing. ISBN978-i-904950-44-viii.

- Kelly, Andrew and Melanie, (editors), Brunel – In Love With the Impossible, 2006 past Bristol Cultural Development Partnership, Hardback ISBN 0-9550742-0-vii Paperback ISBN 0-9550742-1-five.

- Rolt, Fifty. T. C. (1957). Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Longmans. ISBN 0140117520.

- Tyler, David Budlong (1939). Steam Conquers the Atlantic. D. Appleton-Century.

- Verne, Jules (1871). A Floating City. Harper. ISBN978-0-7509-3447-iii. (Account of his 1867 voyage on Great Eastern).

- Wallace, William A. (2014). The Dandy Eastern's Log: Containing Her First Transatlantic Voyage and All Particulars of Her American Visit. Europaischer Hochschulverlag GmbH & Co. ISBN978-3954272662.

- The Titanic Disaster: An Indelible Instance of Coin Management vs. Take a chance Management

External links [edit]

- Smashing Eastern on thegreatoceanliners.com

- The building of the Great Eastern. at Southern Millwall: Drunken Dock and the Land of Promise, pp. 466–480, Survey of London volumes 43 and 44, edited by Hermione Hobhouse, 1994.

- Great Eastern and Cablevision Laying

- Brief description of Corking Eastern

- SS Great Eastern on Facebook

- Get-go voyage of Bang-up Eastern [ permanent dead link ] , in The Engineer, 16 September 1859.

- Images of Bang-up Eastern at the English language Heritage Archive

- Maritimequest SS Swell Eastern Photograph Gallery

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Great_Eastern